“At its best, the sensation of writing is that of any unmerited grace.

It is handed to you, but only if you look for it.

You search, you break your heart, your back, your brain, and then —

and only then — it is handed to you.”

~Annie Dillard

Every December for as long as I can remember, I’ve looked forward to reading reviews of the best books of the year. When my Sunday newspaper arrived I was excited to find the Boston Sunday Globe’s list, “The Best Books of 2017.”

Immediately, the sheer range of non-fiction topics writers write about struck me: true-crime cases, artists’ early years, collected essays, segregation in the U.S., memoirs, and more.

Immediately, the sheer range of non-fiction topics writers write about struck me: true-crime cases, artists’ early years, collected essays, segregation in the U.S., memoirs, and more.

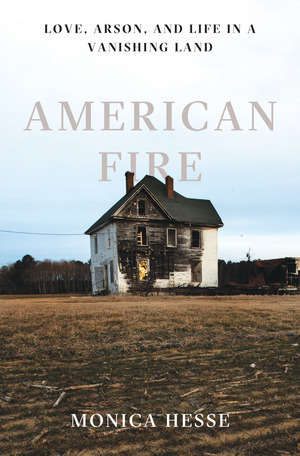

The description of American Fire: Love, Arson, and Life in a Vanishing Land by Monica Hesse caught my attention. I wondered how a writer would begin to tackle writing a book about 70+ fires in rural Virginia and the serial arsonists who started them.

The Story

Monica Hesse, a Washington Post features reporter, first drove to the county to cover a hearing for Charlie Smith, a mechanic who, upon his capture, had promptly pleaded guilty to sixty-seven counts of arson. “As Charlie’s confession unspooled, it got deeper and weirder. He wasn’t lighting fires alone; his crimes were galvanized by a surprising love story.” Over a year of investigating, Hesse uncovered the motives of Charlie and his accomplice, girlfriend Tonya Bundick.

One could suggest that Monica Hesse was “handed” the story as a newspaper feature about arsons in Accomock County. But herein lies the difference.

Another writer might have skated over as dozens of suspicious fires and a community grappling to understand them, but Hesse did not. That’s what makes Hesse’s lessons-learned from writing a nonfiction book most instructive. She quickly assessed that her preliminary research for the news features only gave her a “thumbnail-sized idea of Accomack and what it had meant through centuries…but there were other things about the county that I really couldn’t understand until I moved there.”

Real World Exploration

On the day the Sheriff, whom everyone said she should interview, finally agreed to meet with her, Hesse didn’t come prepared to take notes. Instead, she heeded her mother’s advice to “bring him a pie.” She confesses she actually brought banana bread, which apparently was a worthy and successful substitute for a notebook.

Hesse says, “I just sat in the Sheriff’s office and listened to all the deputies tease each other and tease me. I watched people wander in to sell raffle tickets or share photos of the homecoming dance, and all of that taught me more about what is was like to live in Accomack that anything I could have learned in a formal interview.”

Writing As a Singular Experience

During her two-month stay in Accomack, Hesse didn’t write a word of the book. Upon her return she sat down every day for the next two months and wrote exactly 1,000 words, often stopping mid-sentence and beginning the next day where she left off.

Hesse suggests that writing a book is a singular experience. “The biggest lesson is that there aren’t really any shortcuts for a big narrative project. I could not have written this story if I’d only spent a week in Accomack—or, more realistically, a day in Accomack, which is what a lucky reporter would have been given to write this story for a news organization. I will say that I did not expect to write a book about serial arsonists and have the arsonists come off as sympathetic figures by the end of my reporting. Maybe that’s a useful lesson, not only for long-form narratives but for all writing: If a character seems all bad or all good, you probably don’t understand them well enough yet.”

The 3 R’s: Research, Real-World Exploration, and Review

On the topic of research, Lee Gutkind, editor of Creative Nonfiction Magazine says, “all creative or narrative nonfiction books or articles are fundamentally collections of scenes that together make one big story.

“But to reconstruct stories and scenes, nonfiction writers must conduct vigorous and responsible research. In fact, narrative requires more research than traditional reportage, for writers cannot simply tell what they learn… I introduce [students] to a process of work I call the three r’s: First comes research, then real-world exploration, and finally, and perhaps most important, a fact-checking review of all that has been written.”

Lessons Learned

We learn from Hesse the importance of:

- Taking one’s time to research a story

- Demonstrate authentic interest in the characters as people

- Connect on a personal level

- Talk to people everywhere you can

- Schedule your writing time

- Adhere to a schedule that works best for you

As you continue working on your book, ask yourself: Is there more research you could do or an angle you haven’t yet explored? If you take those additional research steps, will your writing come more easily? Will the writing then, and only then, be handed to you?

Have you studied how writers write? Tell us what you learned in the process by leaving a comment below.

About the Author

Deb Hemley writes memoir, personal essay, short fiction, and articles about social media. She has published pieces in Biographile, Hippocampus Magazine, All That Matters, and Survivor’s Review. You can follow her on Twitter @dhemley.

Deb Hemley writes memoir, personal essay, short fiction, and articles about social media. She has published pieces in Biographile, Hippocampus Magazine, All That Matters, and Survivor’s Review. You can follow her on Twitter @dhemley.

Photo courtesy of bwardpt0 / Pixabay.com